15 Oct The secret science to better performance at running that can totally change your results…

The Science of Running & Recovery with Basecamp Coach and Ambassador Chris Woolley

We sat down with Joe’s Basecamp strength and conditioning coach, endurance athlete and soon to be Guinness World Record holder Chris Woolley. Chris is the man to see about the science of running, recovery and breathing techniques as he keeps his ear to the ground on current breakthrough approaches.

As you read this article to the end, you will learn about Chris’ approach to coaching runners, the secrets of breathing and breathwork explained, the science of recovery and finally how you can find out more.

Here’s what he had to say:

Image credit: Richard McGibbon Photography

How do you approach running technique and style?

Looking at technique and style I would assess someone’s cadence* which is important, but more so, are running mechanics and economy of effort. A 180 cadence is the sweet spot, and some trainers even use metronomes to count this. Actually, everyone looks at cadence. I like to look at it through a different lens. I look at areas including a runners hip extension, their knee lift, a forefoot strike as opposed to heel strike, power off the ground, toe lift, as well as their trunk and ankle angles.

With the right hip extension angle (imagine the angles of those Olympic runners you see in the pictures), your stride length increases. Often good running mechanics will sort cadence out. These combined with a cadence in the area of 175-185 (depending on the runner) will be a good place to start. Then it comes down to power endurance. If everyone has the same running mechanics, whoever has the best power endurance will win.

*Cadence – also known as stride rate – is the number of steps a runner takes per minute. Someone’s height, leg and stride length and running ability will determine their optimal cadence. Everyday runners generally fall between 160-170 steps per minute, while elite runners strike the ground around 180 steps per minute or higher—with some getting above 200 at their fastest speeds

What is the most important components of being a good runner?

It does depend on the type of runner, the distance of their event and years they have been training. A good runner should possess at least the following in as high a degree as possible;

Aerobic base, which energy systems you use are massive. Unless you’re a 100-400 metre sprinter, who doesn’t use oxygen, a good aerobic capacity, a good ability to buffer lactate and to teach the body to clear & buffer lactate are huge components.

Power to the ground and economy of effort are other components. Running economy is generally used to refer to the steady-state consumption of oxygen at a certain running speed and expresses the energy expenditure required to perform at this intensity. If you improve your economy you can go faster for longer.

Lactate tolerance and threshold. Lactate gets a bad rap, actually if there is a buildup of CO2 in the muscles, you can shuttle it out, and there is a process in the body which turns built up lactate into energy.

Lastly maximum sustained power & strength. It’s most important force is going through your body into the ground. The stronger you are, the more durable you will be. It’s a strength to weight to power ratio. This influences the mechanics of the runner. We can work on building that through resilience and restoration work, sled drives and the likes helps.

What’s your approach to strength and conditioning?

It will differ for all runners depending on their strengths and weaknesses. I look into;

- Relative strength, focusing on posterior chain

- Muscular & power Endurance

- Stability, mobility

- Durability/work capacity

- Recovery

- Strength through length. Being strong in the end range movements

How do you approach prioritising events for your athletes / yourself?

I came out of soccer at aged 25 being okay but I was continuously coming 2nd or 3rd. Now I’m dialing in on my events, this year I have been picking sub 30 minute races to compete in. The thinking, being to train the same energy system in all races, thus being a better ‘generalist’ than a specialist in one area of running.

Leading up to the event, I will train the specific techniques I require for that particular race, turning corners up stairs, throwing spears for the spartan race, actual stair climbing etc.

As for the athletes I train, I use A & B events to prioritize important races. The amount of ‘A’ events depends on the athlete and the sport. If you are doing endurance, marathons or ultra’s, you may only have two a year. ‘B’ races are then sprinkled in. It may also depend on the travel commitment and financial cost of the event which classifies it as A or B.

The benefits of the ‘B’ race are adaptations and race experience. You might train through it so you might deload for it (or not necessarily) or taper for 1 week. For my ’B’ races I will take a day or two off so I’m fresh, but I don’t have to be ‘peaked’. In contrast I will deload ten days for an ‘A’ race.

For athletes, races are very important. It’s the reason they train, and in an ideal world, they would roll up to every race able to perform at their maximum physical potential. However, the reality is that the human body cannot maintain the optimal conditions required to perform at this peak for long – 6-8 weeks at most. Peaking requires a balance of fitness and freshness. Through the use of training plans, you’re better able to plan a season so that the “stars align” on the day that your performance is most important.

What’s the latest in breathing techniques?

There are a few things that can be developed for breath work, better aerobic efficiency and Co2 tolerance are starters.

Co2 Tolerance:

The usage of the term Co2 tolerance is somewhat foreign to the exercise world. It is more common place in the arena of free diving where holding the breath is of importance. But training for Co2 tolerance has a place in fitness just as it currently does in diving. Co2 tolerance is at the heart of yoga breathing principles as well. Most of us who think of diaphragmatic yoga breathing think that it encourages deep breathing. Although this is partially true, the real power of yoga breathing comes to bear in how you build up your Co2 tolerance and slow your respiration. Accumulation of Co2 and hydrogen ions in the body are the chief factor in your fatigue tolerance. Little can be done in terms of increasing your tolerance to hydrogen ions, but something can be done to increase your tolerance to Co2. Ironically, Co2 plays an important role in your blood in terms of buffering hydrogen ion production and lactic acid. The problem arises when the respiratory center in your brain has a low Co2 set point.

A low Co2 set point will stimulate you to over breathe during exertion. Over breathing for the amount of exertion you are performing solves one issue of getting you extra oxygen, but it also causes you to over release Co2. This over release of Co2 during exertion accelerates acidosis and makes it exceedingly difficult to maintain intensity levels. A higher Co2 tolerance will equate to a more regulated breathing pattern while under duress. It will allow us to preserve the power output of our breathing musculature for longer periods. Improved Co2 tolerance will also allow us to regulate our breathing so that our bodies have more Co2 available during exertion to buffer elevated acid levels. One of the greatest benefits of improved Co2 tolerance is the reduction of breathlessness while we train.

Respiration Control

Secondly understanding respiration control with breath practice. There are two types, ‘working’ and ‘not working’. The latter involves cadence and apnea exercises, think yoga, pranayama and free diving.

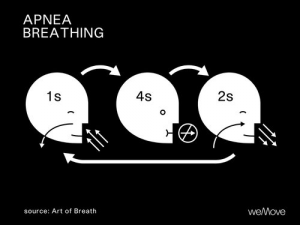

Apnea Breathing – The Down Regulator

Apnea breathing is the down regulator aimed at putting the body into a parasympathetic state. It can be done post workout or at night immediately before going to bed. With nasal breathing only; Inhale for 1 second. Hold for 4 seconds. Exhale for 2 seconds. Do this for a 5-10 minute period.

Cadence Breathing (a version)

This will help regulate a person’s breathing and everyone should be able to get through this with no stress.

Done with nasal breathing only for a 5-10 minute period.

Mark Divine talks about box breathing, which is a four second inhale, a four second hold, a four second exhale and a four second hold. It downregulates the body and brings it into the parasympathetic state. It’s a really great way to start breath work. I think we are all mouth breathers. Box breathing through you nose decreases your resting breaths. Just five minutes in the morning will start to bring your breath count down.

The other ‘non working’ breath exercise is to reset the body which can be used in very stressful situations. It’s a four second inhale, seven second hold and an eight second exhale. Do that four or five times and it completely resets the stress, downregulated the body.

For the ‘working’ breathwork, I use the breath as gears. Normally you have ‘5’ gears, but I make it simple and start with 3. The first gear would be your daily activities, breathing nose in, nose out. The second gear would be mid range, a 10km run, where you are breathing nose in, mouth out. The last gear is breathing mouth in, mouth out. If you can train to move through these ranges it teaches the body to utilise maximum O2 levels in the system. I get people for three minutes on rower and try nose breathing, most beginners can’t do it. If you are in 1st gear until 95% max effort, you can delay all the other changes and get faster and better economy of running.

CO2 and O2 tables

A Co2 table trains you to deal with that burning feeling of needing to breathe, whilst an O2 table trains your body to operate on low O2. These tables are used by freedivers. A CO2 table is basically a series of dives which gives you less and less time to recover in between breath-holds. This slow increase develops your tolerance to CO2. The urge to breathe is mainly triggered by elevated levels of CO2 in your bloodstream. CO2 tolerance is something that freedivers like to build up so that they can delay and reduce the onset of the urge to breathe. The more your CO2 tolerance, the less urge to breathe at the same CO2 level.

Hypoxia work

Going to a hypoxic environment, whether natural or artificial, puts a new stress on the body causing the various systems of the body to react and adapt to its new environment. Training at sea level, similarly causes numerous changes to occur within the body as it attempts to react to the stress of the particular training load. When exercising at altitude, the body not only has to respond and adapt to one stimulus, it has to respond to two, a training and hypoxic one. When these two stressors combine, the body’s primary goal becomes ensuring adequate oxygen delivery to the working muscles. Two main factors will determine the physiologic and metabolic response; the intensity of the exercise and the level of hypoxia.

Lastly for running there is specific cadence development using the rate of perceived exertion doing drills with breath within 5/7/10 second protocols.

What’s the latest in recovery techniques?

I work with a few metrics to monitor and record ongoing recovery. Firstly understanding the Maximum Recoverable Volume or MRV is important. It’s the most training an athlete can effectively recover from and this could vary widely from runner to runner or for the same athlete at different times.

Secondly tracking your Heart Rate Variability or the readiness to train allows you to understand if you have recovered. HRV is the cheapest and easiest way to record and monitor metrics. It’s 70 bucks for a polar strap, coupled with a 10 dollar app. I’ve been using it for 5 years. It’s a measure of the nervous system, both sympathetic and parasympathetic. You’re able to see a trend, and figure out your baseline. You’re able to see if you are under or over and change the session for the day if it’s over. You generally are if you’ve been pushing it for a few days. People train train train train, that’s when injuries occur, people get sick and colds, flus and injuries happen.

The other free way is a baseline breath hold every morning. You breath in, exhale and then breath hold. You figure out your baseline, say it’s 22 seconds, then the next day is 12 seconds. The baseline breath hold measures stress and that drop off in numbers means you’re not recovered.

The other thing I’ve been playing with is cold work. I bought a chest freezer off gumtree, it was 100 bucks. I took it home siliconed it, turn it on for 24 hours, now had a timer for it to turn on for 30 minutes each night. I get in there three minutes per day and my resting heart rate dropped 10% just from this. I won’t do it after a strength session, as it blocks the muscles but I will do it after running a session. Running is something that has broken the muscles and joints, so the benefits of the cold are enormous. I saw a huge change in my recovery and have had 10 mates get chest freezers after seeing my results.

What is it you love about trail/mountain running/running in events?

Chris smiled and simply stated “I feel like I’m free”.

Imagine spending a morning with Chris? How much could you learn… well now you can. An opportunity NOT to be missed!

Join Chris at Joe’s Basecamp for the Running With Chris Woolley Workshop on Saturday 19th October 2019 at 9:30am. Get your ticket here now!

References

On HRV

https://www.trainingpeaks.com/blog/using-heart-rate-variability-to-schedule-the-intensity-of-your-training/\https://f

On CO2 tolernace

orums.deeperblue.com/threads/exactly-what-is-co2-tolerance.17399/

On Hypoxia

https://www.scienceofrunning.com/2010/03/how-hypoxiaaltitude-works.html?v=6cc98ba2045f

Apnea Tables

https://www.caperadd.com/news/what-are-apnea-tables/

On Cadence

https://blog.wahoofitness.com/running-cadence-why-it-matters-and-how-to-improve-yours/

Economy of effort

http://archivosdemedicinadeldeporte.com/articulos/upload/rev2_ingles.pdf

No Comments